Sweden in “The Age of Freedom”

A Former Great Power

As a consequence of the Great Northern War, Sweden lost its former 17th Century status as a great power. By the ceding of territory in the treaty of Uusikaupunki of 1721 Russia now had a new and decisive position in Baltic affairs. The eastern region of the kingdom, Finland, had to take the heaviest burden both in war and peace.

In its weakened state, Sweden had to balance itself between the aspirations of the great powers. England, France and Russia tried to affect both its external and internal politics. Despite this weakening of its military and economic position, dreams of a return to status as a great power were awakened. The War of the Hats of 1741–1743 was however an almost total catastrophe. Finland was occupied once more. After this loss of territory, Finland was more defenceless than ever against Russia.

Polity in The Age of Freedom

For this loss both in human and in economic terms, King Charles XII was mainly seen as guilty, but also the whole system of autocracy. The constitution which was enacted in 1719 and 1720 guaranteed the four estates essential constitutional rights. In practice the king retained his status only as a figure-head.

Behind the new constitution on the one hand were concepts of natural order, according to which the king had not received his mandate from God, but rather from the people, and on the other hand the enduring Swedish traditions of democracy. In the “Age of Freedom” the political system was representative of the most developed form of parliamentarianism, with its only point of comparison being in England.

In addition to the power of legislation and of economics, the Diet’s essential purpose was foreign policy. From time to time the estates of the realm also took upon themselves the judicial powers.

The Council of the Realm had executive power, and its members were chosen only from the nobility. According to this Form of Government the Council of the Realm was responsible to the estates of the realm. A notable move in the direction of modern parliamentarianism was that the Council of the Realm (members of the government) began to be dismissed with the change in the balance of political power.

Population

The growth in population in the Sweden of the 18th century was rapid. From 1721 to 1800 the population doubled. Finland’s proportion of the total population rose from 17 to 26%. At the end of the century there were some 900 000 persons living in Finland.

The eighteenth century however brought no great improvement in nutrition and healthcare; the rate of mortality was high, but the birth-rate was even higher.

Apart from growth, population questions were the main concerns of the age of freedom. The Swedish Tabellverket was founded in 1749, and began to keep a regular population register – the first in the world.

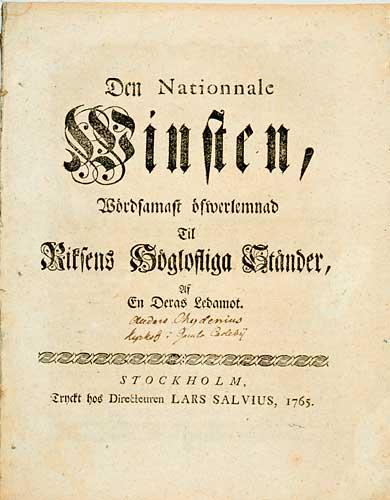

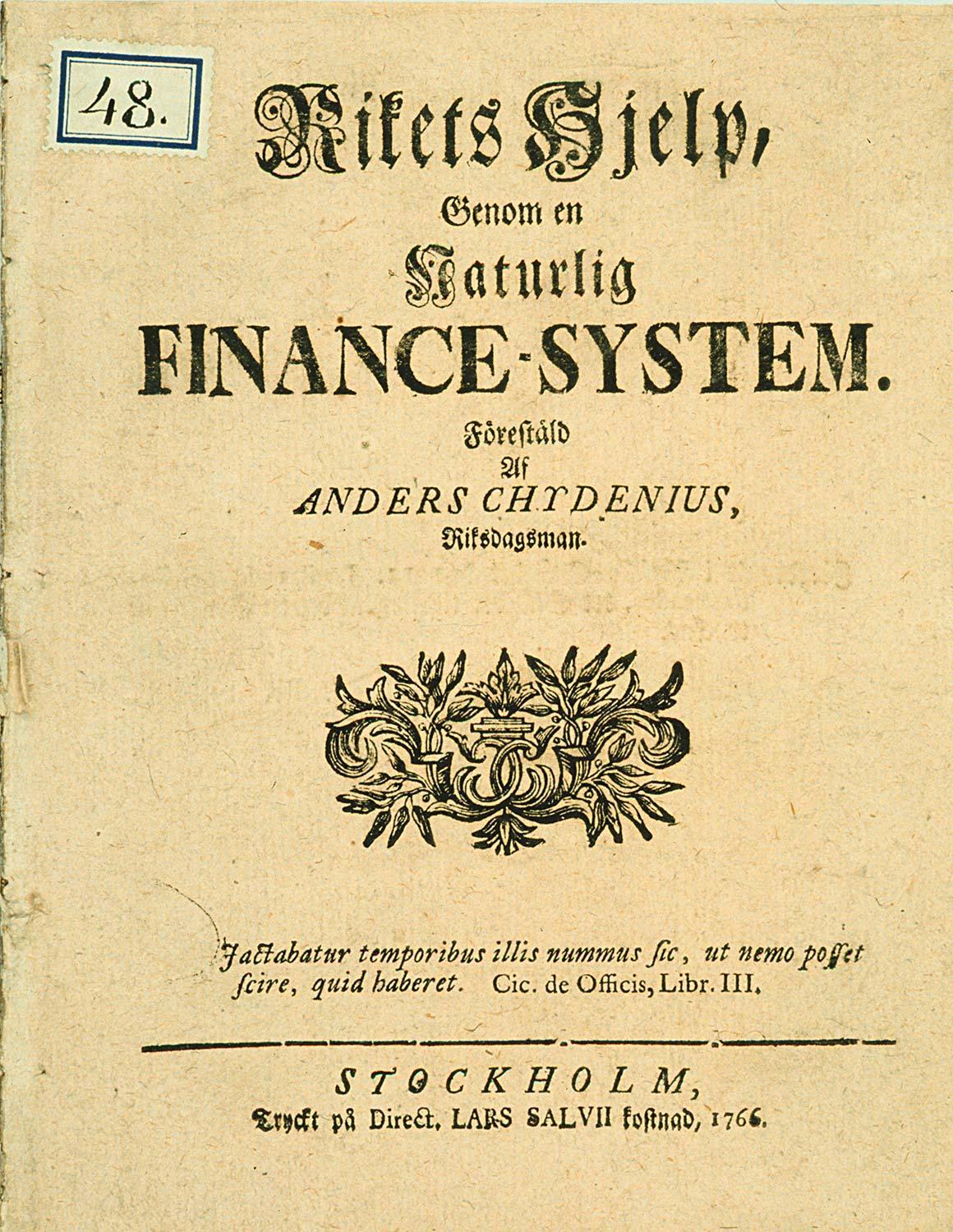

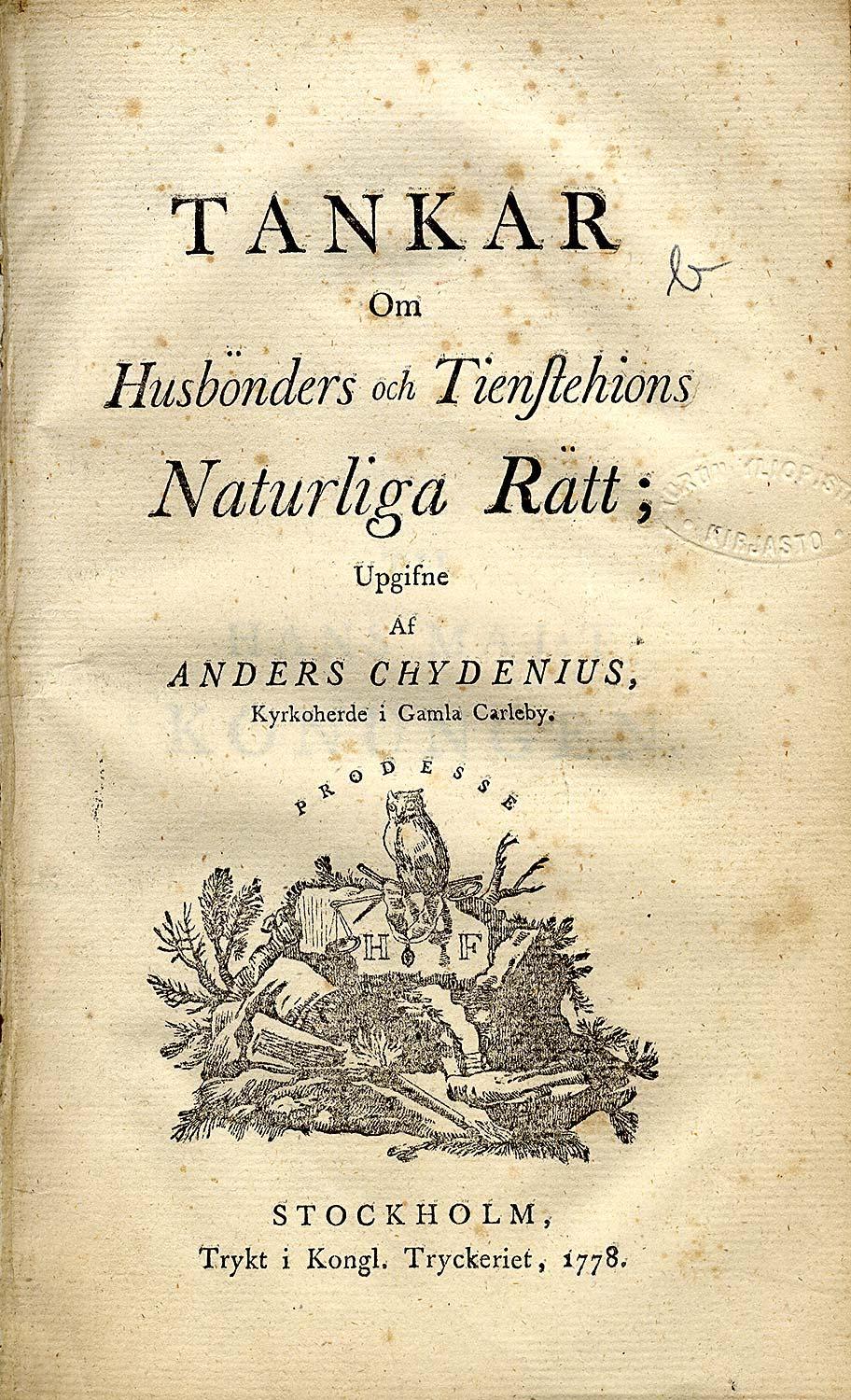

The actual population number turned out to be much smaller than had been assumed. After this ensued a debate on emigration, assumed to be considerable. Anders Chydenius participated in the discussion with his prize essay in 1763.

Means of Livelihood

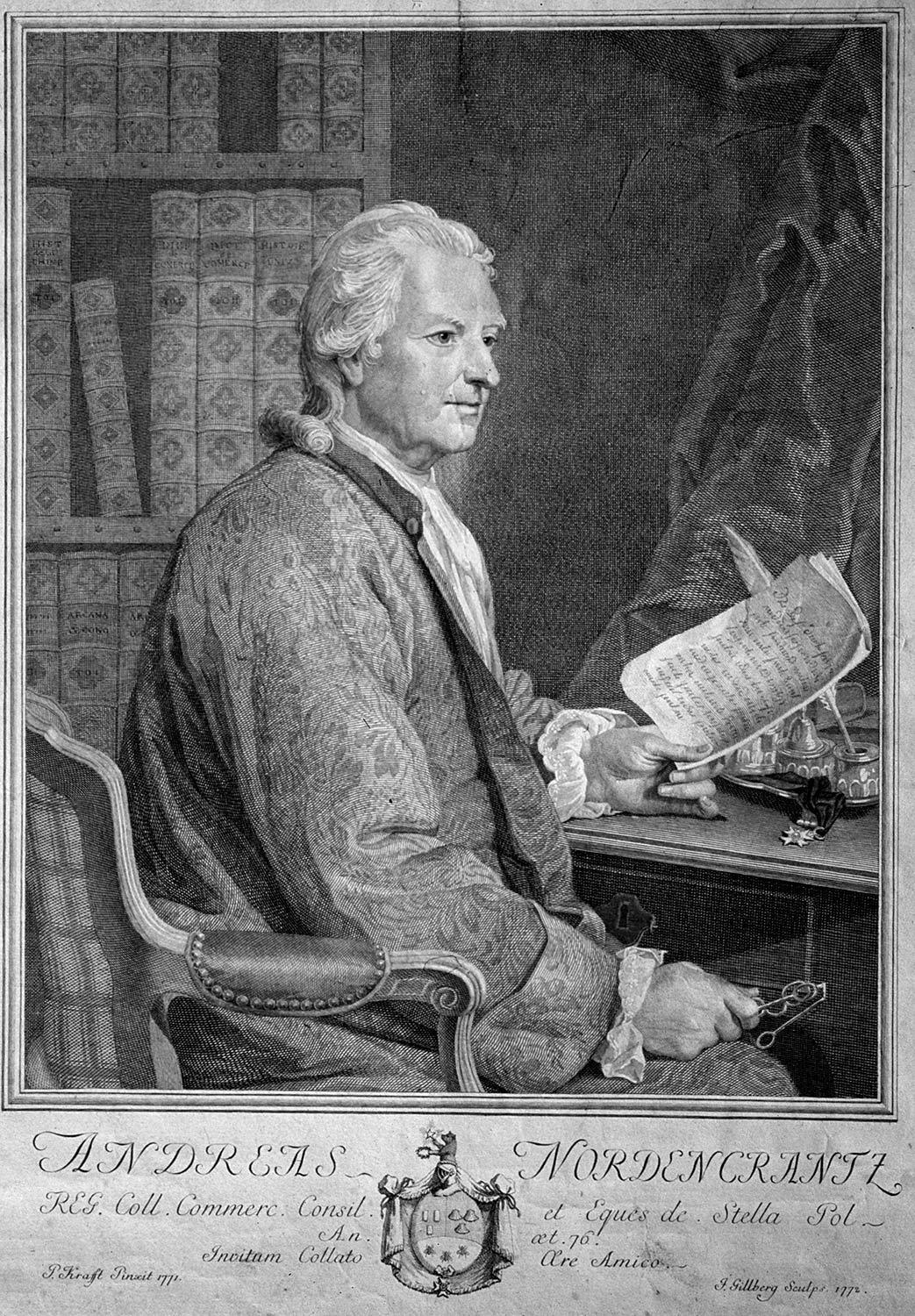

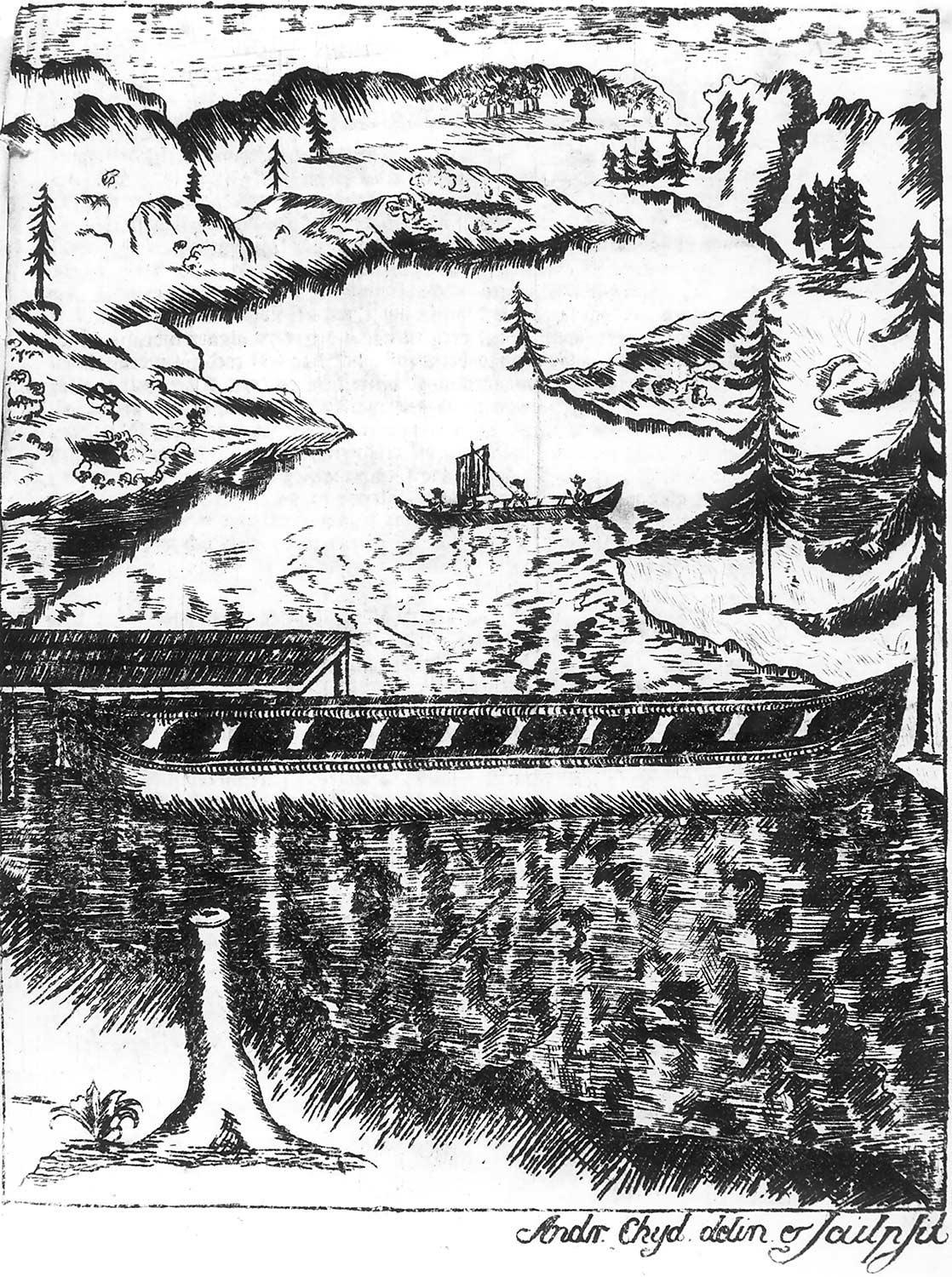

Tar-burning pit as portrayed in Edward D. Clark’s ‘Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa’, London 1824. The National Library of Finland.

During the eighteenth century some 75–80% of the population of the whole realm earned its living through agriculture and its subsidiary trades. In Finland more than 90% lived by agriculture. The situation hardly changed at all in the course of a century. Neither did the productivity of agriculture rise at all, despite the activities of the enlightenment and innovations, during the Age of Utility.

In local patches, various subsidiary means of livelihood were significant to the peasant economy. In Ostrobothnia tar-burning rose to a central position due to the availability of the raw materials, and to the transport ways offered by the rivers. Tar, which was in demand due to numerous wars and the conquests of colonies, was Finland’s most important export product, with great significance also for the development of the Ostrobothnian towns.

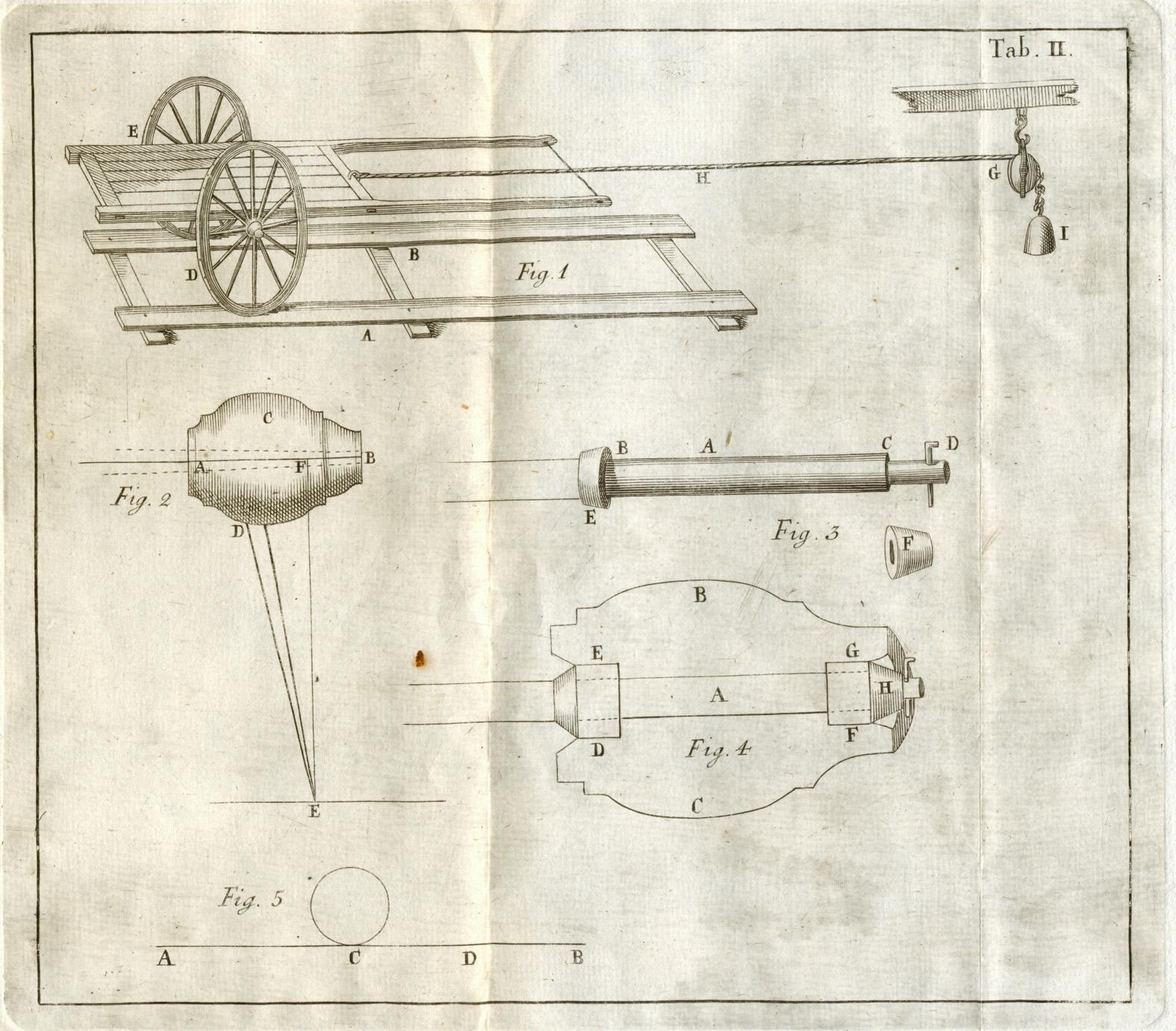

At the end of the eighteenth century, Finnish ships were almost as valuable an export item as tar. Most of them were sold to Sweden, but some also to foreign lands. Shipbuilding was concentrated in the areas in and around the same towns of Kokkola and Pietarsaari, where there was trading in tar.

The economic policy of the Hats (hattar) Party, so long in power during the Age of Freedom, supported iron production and manufacture, and various kinds of “industry” were also started in Finland by means of subsidies. The importance of this was however very little. The total economic value of Swedish production in iron was a good deal. Britain, for example obtained 60% of its iron from Sweden in the mid-eighteenth century.