The Struggle for Freedom of the Seas

The Staple Trading Towns

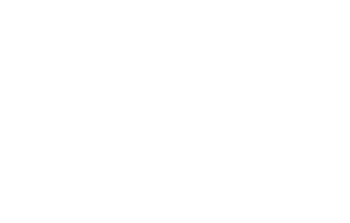

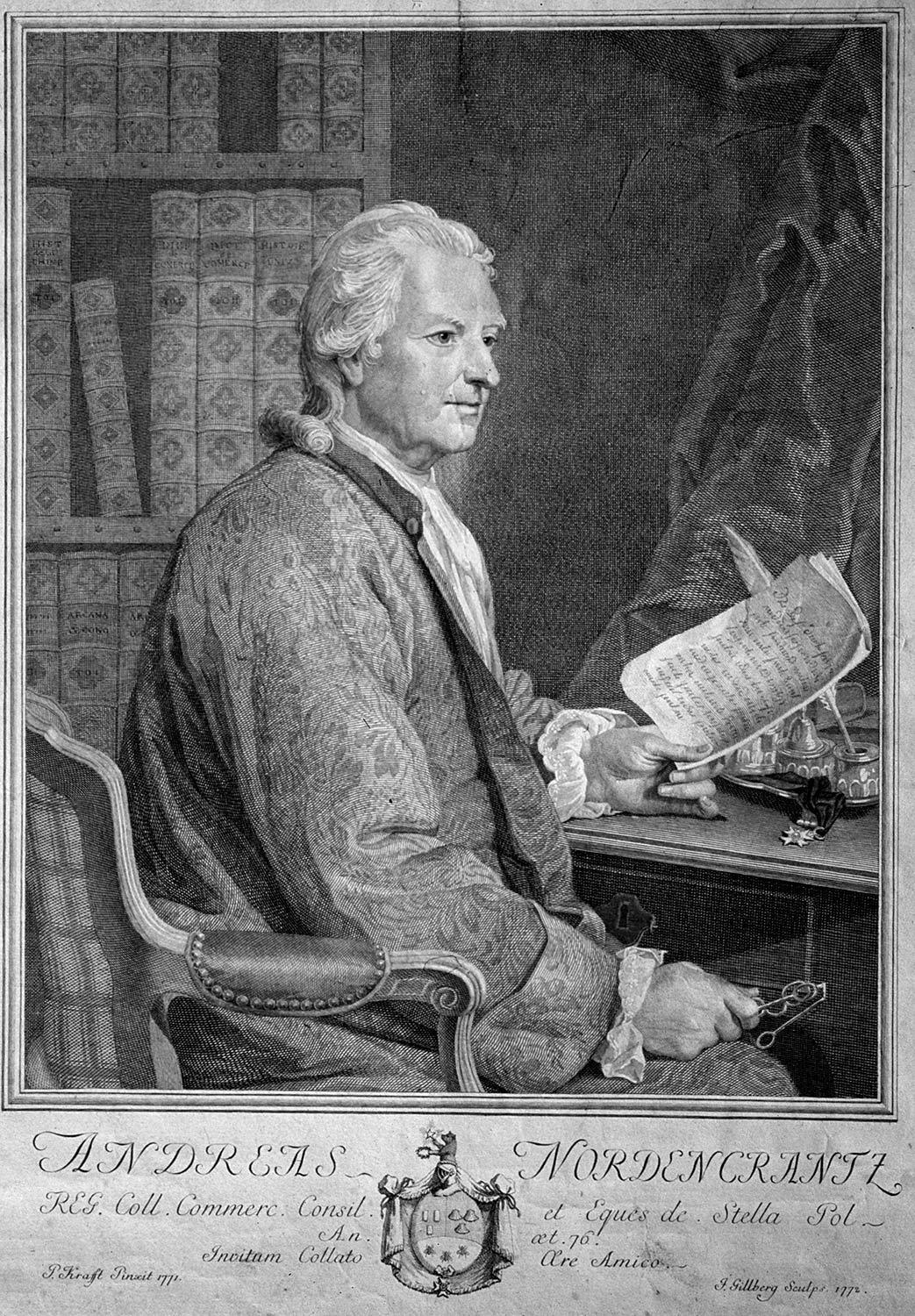

The Navigation Act of 1617 forced the traders of Ostrobothnia to bring their export wares to only two staple towns with export trading rights: Turku and Stockholm. This centralisation of foreign trade was a policy typical of mercantilism, and behind it were the richer merchants of Stockholm and their monopoly syndicates. Efforts had been made to get the matter changed since the end of the seventeenth century by delegates from both Ostrobothnia and Västerbotten (West Bothnia).

At the Diet of 1760–1761 the delegates from Ostrobothnia – and particularly the magistrate Petter Stenhagen from Kokkola – were active. The necessary support of three estates was obtained, but the matter was left for the Council of the Realm to resolve.

Chydenius’ Role

Anders Chydenius, having been remarked upon in Kokkola as an enthusiastic defender of freedom and a forthright speaker, was one of those sent to the Diet to oppose the restriction of trading. Right at the beginning of the session of the Diet, his essay against trade restriction was issued. Chydenius rejected the claim of the Burghers that restriction of trading was a question of the privileges of their station. In addition Chydenius showed what damage the concentration of economic power in the hands of Stockholm’s wealthy Burgher class brought upon the whole of society. The decision to grant foreign trading rights to the towns of Kokkola, Oulu, Vaasa and Pori eventually gained the support of the required minimum number of three estates.

Chydenius’ influence upon the attainment of staple trading rights is often overemphasized. He became involved only at a stage by which a decisive step had already been taken. The activities and writings of Petter Stenhagen had already had a distinct effect. However, Chydenius’ incisive propaganda had great influence – it encouraged the defenders of freedom of navigation, whilst discouraging its opponents.

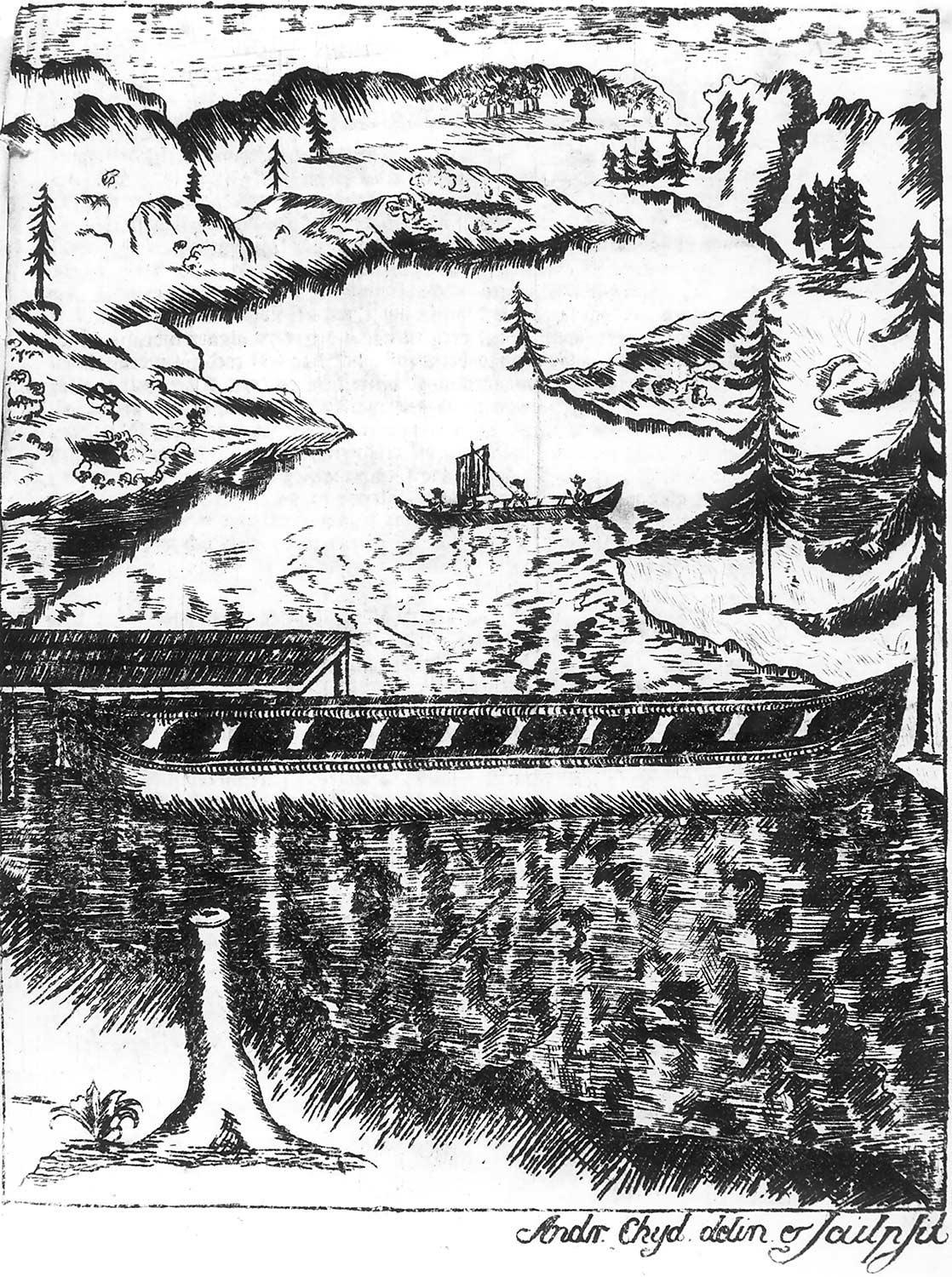

A New Struggle

In 1774 the Government presented a surprise plan for the concentration of Ostrobothnia’s foreign trading through the town of Kaskinen, to be established near Kristiinankaupunki. The staple trading rights of the other towns were revoked, according to plan. Behind this, once more, were the interests of the wealthy merchants of Stockholm. The plan aroused anxieties in Ostrobothnia. Anders Chydenius published an essay in which he demonstrated the great significance of staple trading rights for the welfare of Ostrobothnia and of the whole realm. Chydenius’ activity apparently had a more decisive influence in 1774 than in 1765. By a decision made in 1777, Kokkola and Oulu were allowed to keep their staple trading rights.

The freeing of foreign trade greatly affected the future development of the Ostrobothnian towns. Above all, the shipbuilding and tar-exporting trades, closely linked with shipping, grew remarkably. By its peak year, in 1830, Kokkola’s fleet was the largest in Finland.