Science and Utility

The Breakthrough in the Natural Sciences

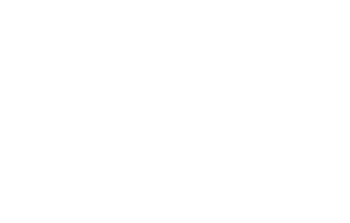

The practice of Science in Sweden had during Carolinian times served primarily the interests of orthodox religion and the centralised State. The revolutionary new ideas and observations had not yet managed to enter the universities, which tended to concentrate on theology and ancient languages.

In The Age of Freedom the new political and social views also gave Science the goal of total practical utility to society. Above all the eighteenth century meant a huge development in research in the natural sciences as a result of enthusiasm for Locke’s empiricism and Newton’s mechanics. Especially with the ascent into power of the Party of the Hats, the practice of science began to be strongly supported. At Uppsala, Lund and Turku special professors’ chairs in Economic Studies (hushållningslära).

At the same time the achievements of European Science began to upset religious orthodoxy. The disintegration of the world picture of the Old Testament and developments in natural science demanded a new theological outlook. For a long time the philosophy of Leibniz’s pupil Christian Wolff dominated Sweden’s universities. This aimed to show that there was no contradiction between the biblical message and the explanations of the world offered by natural science – the total order present in Nature actually proved the existence of God.

Linnaeus and Others

Carl von Linné (or Linnaeus, 1707–1778), professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala University, through the system of classification of plants which he developed (Systema Naturae, 1735–68), became one of the best known European scientists. His influence extended also far beyond botany.

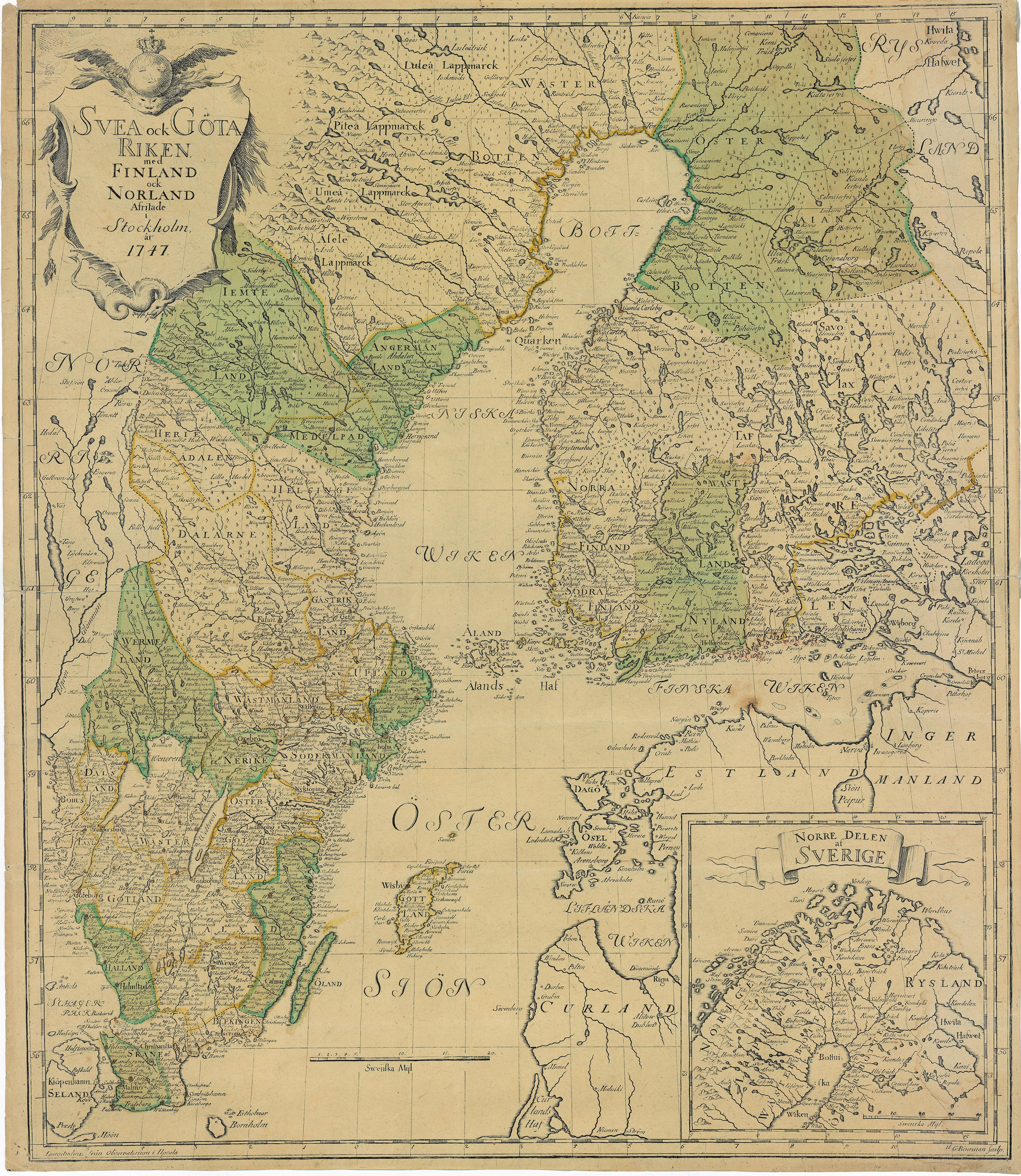

Linnaeus’ Nature existed for the benefit of human beings. The exploitation of Nature and scientific research were to Linnaeus in no way contradictory with the Will of God.

Linnaeus undertook pioneering research and collecting trips to various parts of Sweden. He sent his “pupils” off around the world – Pehr Kalm to North America, Petter Forsskål to Arabia, Carl Peter Thunberg to Japan, etc.

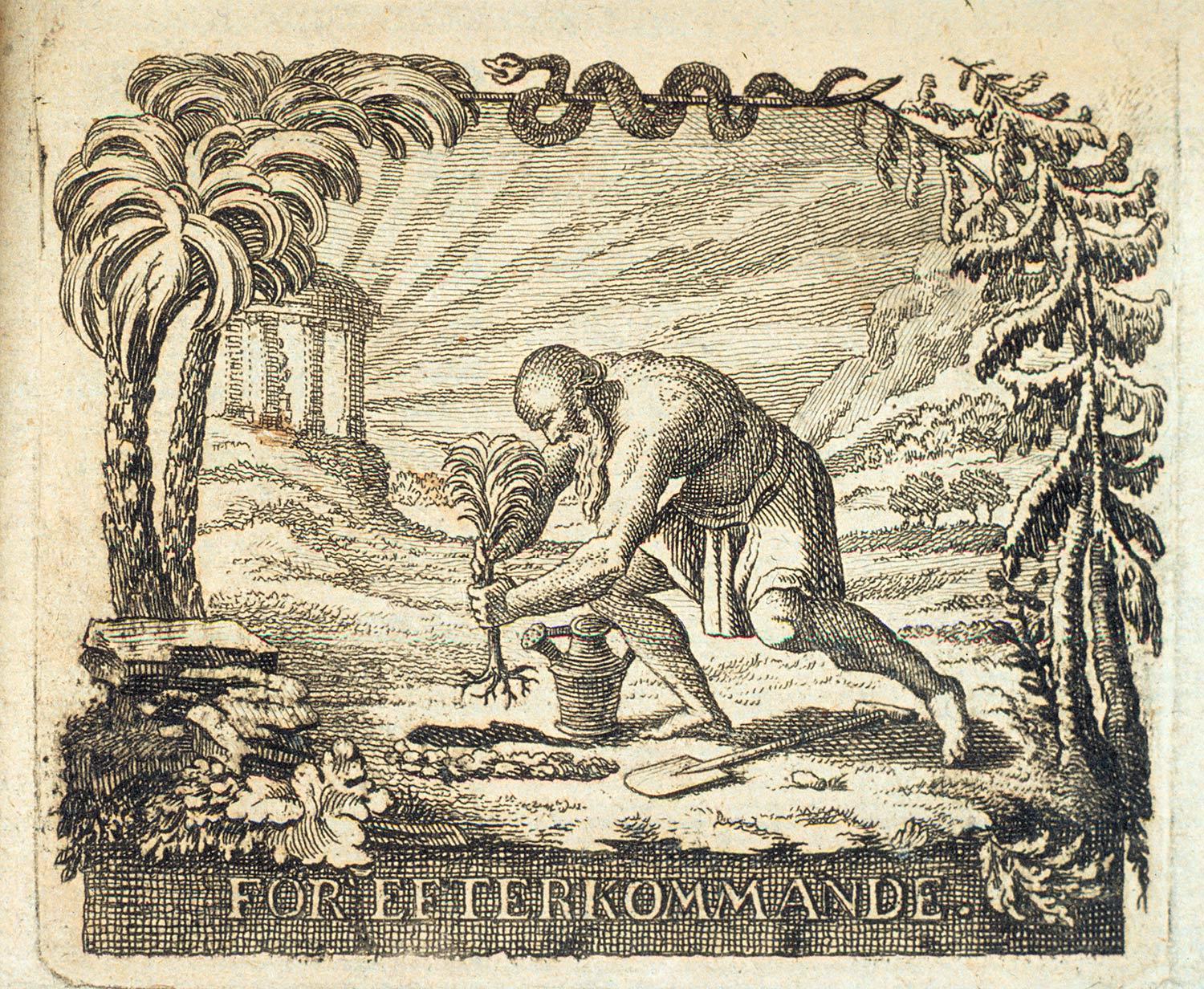

Besides Linnaeus, many other scientists were active, who were making Sweden a leading country in the field of the natural sciences. Anders Celsius and Pehr Wargentin carried out pioneering work in astronomy, although Celsius is better remembered for his thermometer, and Wargentin for his population statistics. Samuel Klingenstierna raised the level of both mathematics and experimental physics into the international league. In view of the national importance of the mining industry, it was natural that mineralogy, and with it chemistry, should attain a central position. Axel Fredrik Cronstedt and Johan Gottschalk Wallerius did pioneering work in the analysis and classification of minerals. Research in chemistry began to flower in the Gustavian period, when Tornbern Bergman and Carl Wilhelm Scheele were working at Uppsala, both esteemed scientists of their time in Europe.

The Universities and Academies

The realm of Sweden had four universities in the eighteenth century – at Uppsala, Lund, Turku, and Greifswald (Western Pomerania). There were four faculties at each : theology, law, medicine and philosophy. All studies commenced at the faculty of philosophy.

The results of scientific research were publicised at disputations. The master thesis often represented more the professor’s than the students viewpoints. The language of the thesis was Latin, although already by the middle of the century, in economic studies, the language began to be Swedish as well.

Although the universities were going through a flourishing period, above all in the natural sciences, their main function was still the training of priests and officials. Many steps forward in science were taken under the auspices of the Royal Academy of Sciences, which was founded in 1739. Its purpose was to promote the natural sciences first and foremost, and their application to economic life. The Academy held great significance as the upholder of the spirit of the Age of Utility.