About transparency and freedom of expression

Freedom of the press

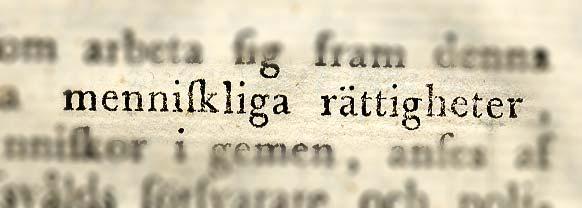

It requires no proof that an equitable freedom of writing and printing is one of the firmest pillars on which a free government may rest; for otherwise the Estates can never possess the requisite knowledge to institute good laws, administrators of the law will be subject to no control in the performance of their offices and those under its jurisdiction have little knowledge of the requirements of the law, the limits of official power and their own obligations; learning and good sense will be repressed, coarseness of thought, expression and manners gain acceptance and within a few years a horrific darkness will settle over the entire firmament of our liberty. But on what basis that freedom should rightly be established, so that on the one hand it cannot be suppressed by any one individual nor on the other hand decline into an arbitrary frenzy, is something that requires more careful consideration.

Memorial on the Freedom of Printing (1765), p. 416r. Translated by Peter C. Hogg.

The most precious possession of a free country

But I worked on nothing as assiduously during this Diet as on the freedom of writing and printing. The writings of Nordencrantz had already opened my eyes so far that I regarded it as the most precious possession of a free country.

Autobiography (1780), p. 144. Translated by Peter C. Hogg.

Freedom of the press comes first

The freedom of the nation is always proportional to the freedom of printing it possesses, so that neither can exist without the other. To the extent that a nation is free, its freedom of printing will be the same, but on the contrary, where printing is muzzled by some form of guardianship, it is an infallible sign that the nation is fettered, as one observes that even under autocratic governments where freedom of writing and of speech are tolerated, subjects enjoy more of their civic rights than in certain states where thoughts and reason have been curbed by restricting printing, although they are otherwise reputed to be free.

Knowledge and power

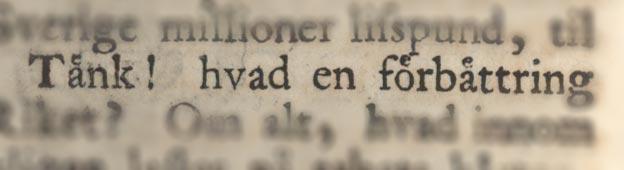

As pleasant as day is compared to night, light compared to darkness, sunshine compared to thunder and lightning, so exciting to citizens is knowledge of their well-being and distress. For that reason, learned subjects are pursued, writers are roused to compete with each other and the printing press exhibits their thoughts. Free societies in particular need such information. They have to manage their welfare by themselves. If they are benighted and leaderless, they will fail to reach the goal of felicity, will hit the rocks and plunge their entire native country into an unfathomable abyss, just when they thought they were about to drop anchor off the shore of happiness. They will then learn how hazardous it is to be a pilot in unknown waters and a leading seaman with no knowledge of the compass.

Sweden has indeed experienced this to its own detriment. Scarcely had a pale aurora borealis appeared in our sky than we thought that it heralded the delightful red light of dawn; a small signal fire, a shining meteor that burns for a few minutes has often captivated us so much that, before we knew where we were, we had strayed from the correct fairway. We have believed them to be sparkling rays from the island of the blessed, but after admiring these quickly extinguished flares for a while, we have found ourselves surrounded by breakers and high cliffs. Most people were completely at a loss, abandoning both sails and rudder, others said that we would soon be able to anchor in a desired haven, but those who were clear-sighted said that the vessel would perish unless we changed course.

It is not enough in free states for a few to have fathomed this. It is the majority that will decide matters. Those who have advanced that far are too elevated above the common people: they are individuals who, once they have gained the confidence of the country through their zeal, are soon led astray from the right path by an insidious self-interest; they should therefore be honoured, but not worshipped, and be followed, but not blindly.

If that is to happen, the nation itself must be enlightened, but that requires reasoning. That is best developed when we put our thoughts down on paper. But there is little encouragement for that unless the printing press makes it public. That provides a noble defence for truth and innocence. Virtue is not sullied by the black stain of slander; it is purified from dross and shines twice as brightly. It is unafraid of daylight, never suspicious of enlightenment and least of all fears any setbacks when that is allowed to prevail.