Music at the vicarage

The photos in this article are from the Anders Chydenius Collection album release concert of the Ostrobotnian Chamber Orchestra in Kokkola, 24 January 2020. Photo Ulla Nikula.

Niamh McKenna (flute), Teija Pääkkönen (violin), Hanna Pakkala (viola) and Lauri Pulakka (cello). In the background Elina Mustonen and Rabbe Smedlund. Photo Ulla Nikula

In 1774, Anders Chydenius, then vicar of Kokkola on the eastern coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, sent a letter to the Royal Academy of Music founded a few years earlier in Stockholm. He had, he wrote, embarked on the cultivation of music in the locality. To that end, he had arranged concerts at his home once or twice a week; a few young people were so proficient that it had been possible to hold public concerts and to charge an admission fee of two copper thalers in order to establish some kind of fund for this musical undertaking. He had also given singing lessons to two girls whose voices “were not unpleasing”, in order to render the concerts more “pleasurable”, and he went on to ask whether he might send the girls to study by “the right method” at the Academy in summer 1775.

Public concerts had first been held in Finland in the early 1770s. This was relatively late compared with the western regions of the Swedish Kingdom (of which Finland was then part), to say nothing of the rest of Europe, and naturally centred on the town of Turku – on the southwest coast and Finland’s leading city at the time. How come concerts for which a charge was made were now being held in a remote vicarage far away up the coast?

Many things were changing both in the Kokkola region and all over Europe in the 18th century. The favourable economic trend meant the rise of the bourgeoisie, representatives of which were assuming positions in sectors of society that had previously been the exclusive domain of the aristocracy. The borders between the classes or ‘estates’ and the prevailing hierarchy became less sharp and social life was increasingly determined according to lifestyle and consumption.

Two seemingly contradictory yet closely interwoven phenomena emerged as a result. One was a new emphasis on the individual and the other a new kind of membership of the community. This way of life required open forums in which to create and maintain new, more subtle social classifications. The new public sphere became manifest in, for example, associations across class borders and public debate in the form of the press. Music was, it has been suggested, one of the first of such forums for “equality”, but also for a new kind of differentiation.

CENTRE AND PERIPHERY

The above is a sweeping generalisation of what was going on all over Europe and mainly applies to the cities. So was Chydenius’s “provincial orchestra” just a historical fluke? Kokkola lay far beyond the influence of the royal court, which in the reign of Gustavus III in particular strongly affected the lives of the upper echelons of society.

The Parish of Kokkola was very big. Thanks to its tar burning and ship building, both closely tied to the world economy, it was notably affluent.

In keeping with the mercantile way of thinking, trade in the region was confined to a fenced-off area, in a town which only the bourgeoisie were privileged to engage in business. In the 1770s, Kokkola had a population of about 1,300, most of them servants, labourers or seamen. Only a few dozen members of the gentry actually engaged in trade. Both the Town and the Parish of Kokkola were presided over by the same vicar, and the church and the vicarage were both within sight of the town.

The role of the coastal towns on the Gulf of Bothnia had, within the trade hierarchy, been to supply raw materials to Stockholm and to its merchants engaging in foreign trade; the former did not have the right to sail abroad and export direct. This had long been considered unjust, because the profit on the growing demand for tar seemed to go straight into the middlemen’s pockets. Since ships able to sail in foreign waters were also being made in Kokkola for clients in Stockholm, it became increasingly obvious to the local merchants that they could handle the whole business on their own.

When the sailing for export ban was finally lifted in 1765, one of those raising triumphant voices was a man from Kokkola, a certain Anders Chydenius at that time chaplain of Alaveteli some 15 miles from Kokkola. The granting of trading rights meant that the world now lay open to the small-town bourgeoisie in both the commercial and the psychological sense: they were now more closely in touch with the European way of life.

The fight for sailing for export rights led Chydenius into politics and the basic issues of a changing society. Coming from the periphery, he could clearly see the decisive influence the newly-acquired freedom and open interaction would have on the development of not only business but of society as a whole. Not being mentally tied to hierarchies, he could leap over several stages of development and envisage the equal society his contemporaries denounced as democracy. Chydenius’s ideas were reasonable in the humane but not always the political sense; from our present-day perspective, he was very much ahead of the times.

FORERUNNERS OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT

The actors, Elina Mustonen (who also played hapsichord), Juha Vuorinen and Rabbe Smedlund. Photo Ulla Nikula.

Spreading enlightenment and new cultural influences in the Kingdom of Sweden were above all the clergy, whose authority grew the further they were from Stockholm. It was not just that they were, in many places, the only people with a higher education. Society was regarded as being a hierarchical system in which each individual had a specific place. Being a vicar was not an “occupation” in the present-day sense; it was the vicar’s duty, as representative of the “learned estate”, to maintain and oversee an order ordained by God.

In the rural regions, the clergy were also leading figures in the secular administration, and they might have great influence over the untutored peasants. They were also part of a network that covered the whole of society, and an efficient channel for disseminating both official and unofficial information. On the other hand, as the standard of living rose in the 18th century, the clergy also adopted a way of life deemed fitting to their estate. This included various forms of socialising, and the vicarage became a local centre of education and culture.

ORGANIST AND ORGAN

It is no coincidence that the early orchestra was born in Finland in Kokkola. A large organ and an organist had been installed at the town’s church in the late 17th century. Anders Flintenberg (1712–1770), organist from 1737 to 1770, had a considerable influence on musical life in the town. He left what was for the times a large collection of 16 instruments from which it was possible to form a variety of ensembles. In general, organists also directed the music in their towns in the 18th century and might be called upon to perform in homes and on various occasions. This was undoubtedly the case with Flintenberg, since there were virtually no other professional musicians in the vicinity. Some kind of orchestral activity may even have existed on a small scale around him.

There is no documented evidence of any connections between Chydenius and Flintenberg; the latter died in spring 1770, shortly before the former took up office. Chydenius had, however, spent a lot of time in Kokkola, for his father, Jakob, had been vicar there from 1746 to 1766 and he himself had been chaplain at Alaveteli until 1770. Anders Chydenius probably came within Flintenberg’s sphere of influence in some way or another. In any case, the prerequisites for an orchestra – instruments and people to play them – were already in place when Chydenius took up his position as vicar in 1770.

ORCHESTRA AND PLAYERS

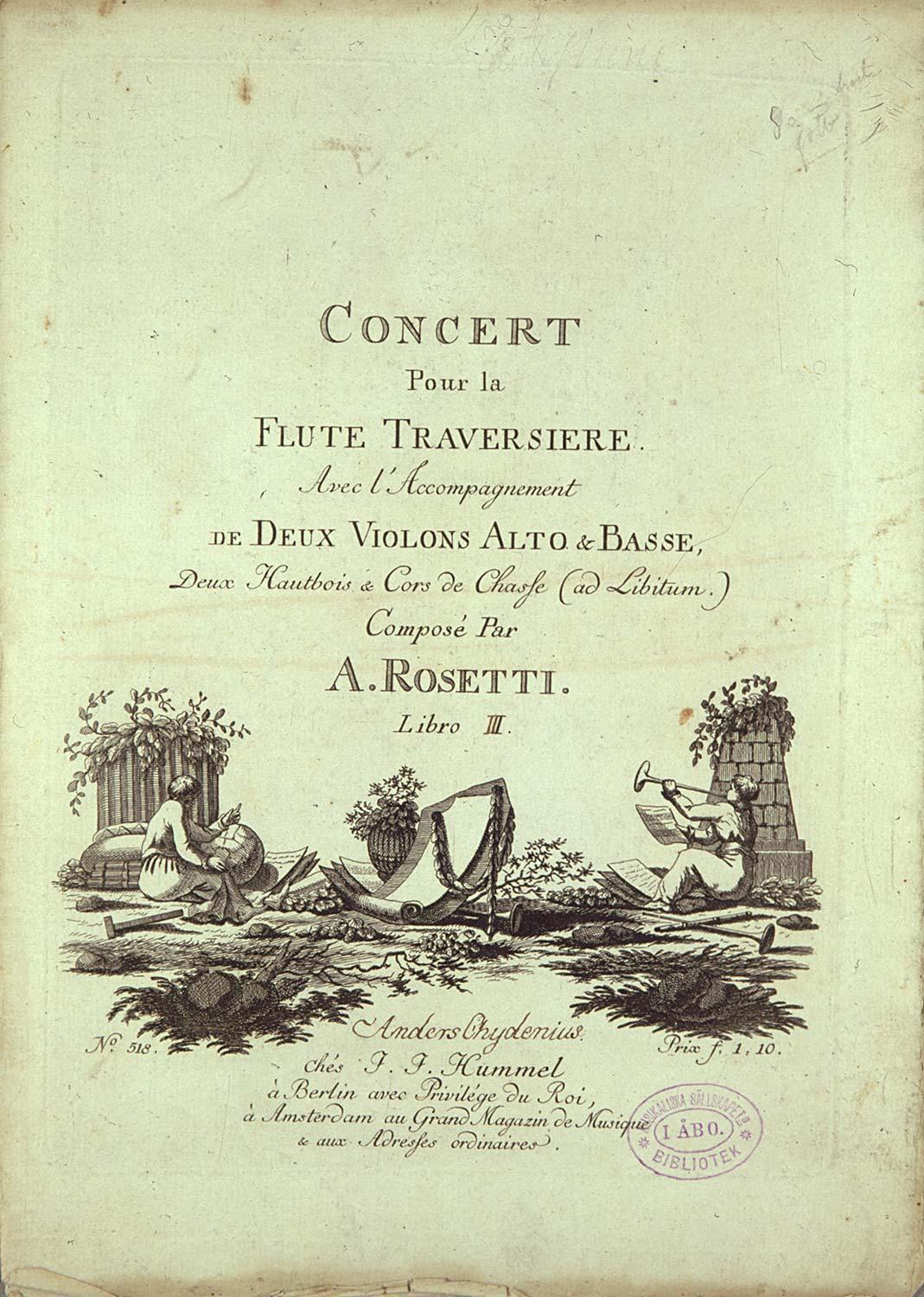

Only one member of the orchestra is known for certain, but he was all the more important. He was Anders Chydenius’s nephew Jacob Tengström (1755–1832), who stated that he played the flute in his uncle’s “musical chapel” (musikaliska kapell), at least in 1775–1777. It is also known that Chydenius had a close relationship with his nephew, and that he supported him at various stages in his career. The relationship may have been bidirectional, for Tengström, who had begun his studies in Turku in the early 1770s, possibly encouraged his uncle to heed the example of the “outside world” in fostering new forms of culture. In any case, Tengström’s later work as founder and organiser of the Musical Society of Turku proves that he grasped the potential significance of such activity.

The identity of the other members of the orchestra is open only to conjecture. One very probable member was the parish chaplain Johan Snellman (1741–1800). Proof of the respect he enjoyed in musical circles is the fact that he had been music teacher to the son of Bishop Mennander and inspector of the Turku Cathedral organ. In Kokkola, he was the first in Finland to import sheet music for the needs of both Chydenius’s orchestra and the Musical Society. In this he was a concrete manifestation of the cultural dimension of the new sailing for export rights. Snellman’s own instruments were at least the flute and the clavichord.

Flintenberg, who served as organist in Kokkola right up to 1801, was succeeded by his apprentice Henrik Kahelin (1736–1805). The only professional musician in the region, he was a natural candidate for Chydenius’s orchestra. No direct proof of this exists, but like his predecessor, he was also the town’s director of music and in addition to keyboard instruments probably played at least the violin.

The orchestra’s main objective was, according to Chydenius, to train youngsters in the art of playing. (Semi-)professionals such as Snellman and Kahelin may have constituted the orchestra’s core and also taught.

Were there any offspring of the gentry in the orchestra? One of the few merchant’s sons known to have been involved in music was Anders Röring (1752–1788), who played the cello. He may have belonged to Flintenberg’s circle and while studying in Turku in the 1770s possibly played in Chydenius’s orchestra during the holidays. He was unusual for a son of middle-class parents in aiming at an academic career. There may, however, well have been others. In order to finance his studies in 1775–1777 – i.e. during the time he played in his uncle’s orchestra – Jacob Tengström held a school for the sons of Kokkola merchants. Among the subjects he taught were modern languages such as French, German and English, history and geography. The syllabus was, in other words, a clear alternative to the Classics taught elsewhere in Kokkola and aimed on the one hand at a general education and on the other at enhancing the practical skills required for engaging in foreign trade. There is no mention of music, but Tengström at least would have been in a position to pick out interested pupils.

BRINGING PLEASURE TO THE HOME

Katariina Heikkilä (alto) and Johanna Isokoski (soprano) singing Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater. Photo Ulla Nikula.

Then what about women? Chydenius had written to the Royal Academy of Music in 1774 with the specific intention of being able to send two girls to study singing in the capital. The request was refused because the Academy’s resources for providing training of any kind were initially limited and the first female students were not admitted until 1795. This was also the year in which women were first permitted to perform at a concert given by the Musical Society of Turku.

No one knows who the girls were, but some conjectures may be made. The most likely candidate was Johan Snellman’s sister Christina (1753–1833), who was living at the vicarage as assistant and companion to Mrs Chydenius. Also staying at the vicarage was Anders Chydenius’s half-sister Helena (1756–1828). In any case Chydenius was hoping to send ordinary daughters of clerical or middle-class families to Stockholm. Something that had previously been considered fitting for the aristocracy was now deemed fitting for these girls – at least in Chydenius’s opinion. And the aim truly was not specifically to increase “pleasure” in the home – the reason why the daughters of the aristocracy took music lessons – but to train for public performance. These were probably the singers who appeared at the inauguration of nearby Teerijärvi Church in 1775.

Chydenius’s family obviously took a liberal attitude to the crossing of gender boundaries. Anders and his brothers had taught their sister Maria mathematics, botany and other subjects to such a high standard that she could then teach her own son, Jacob Tengström. However, girls were not, it seems, allowed to play in Chydenius’s orchestra, at least in public.

PUBLIC AND “IN PUBLIC”

A big event was held in Kokkola in 1778 to celebrate the ratification by King Gustavus III of sailing for export rights to the town the previous year. In addition to being a tactical tribute to the King, it served as a means of engendering a community spirit among the gentry. Such was also the aim of the speech made by Ander Chydenius, in which he urged the gentry to join together in exploiting the economic opportunities afforded by the war in North America. The gentry gathered in two buildings and the day was celebrated with cannon fire, toasts and music. In keeping with contemporary custom, it ended with a ball.

Chydenius’s orchestra possibly provided the music, or at least some of it, and there were undoubtedly more such occasions. Though a public event attended by “all”, it cannot be classified as a new form of middle-class socialising, a “public concert”. The role of the music was here to create and maintain a festive mood; it was not designed to bring audience and performers together.

Were the concerts arranged by Chydenius at his vicarage truly “public”? Yes and no. He had everything he needed to give concerts: a trained orchestra with professional reinforcements, sheet music sent from Amsterdam to Finland’s only music shop, a suitable room (the big vicarage salon), and an audience if not expert at least with money in their pockets. To the outside observer, these events might well have looked like “public concerts”.

Again, Chydenius set out to put a “reasonable” and “beneficial” idea into practice, but reality was not quite able to keep up. The “bourgeois way of life” had not yet taken root for the simple reason that there were so very few who might pursue it. Concerts began to dwindle possibly in the late 1770s already, and the embittered Chydenius sold his sheet-music collection to the Musical Society in 1790. In the emerging market for ‘entertainment’ and free-time activities, Chydenius’s concerts represented an active supply rather than a true demand.

Pertti Hyttinen

Pertti Hyttinen is a historian working at the Kokkola University Consortium Chydenius and is an expert on Anders Chydenius.

Bibliography

Andersson, Otto, Musikaliska sällskapet i Åbo 1790-1808, Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland 1940.

Hannikainen, Päivi-Liisa, Pohjanmaan musiikkikulttuuria menneiltä ajoilta: musiikin taitajia ja tukijoita eteläisen Pohjanmaan kirkkomusiikkielämässä 1700-luvun jälkipuoliskolla, [Helsinki]: Sibelius-Akatemia 2008.

Jonsson, Leif & Anna Ivarsdotter-Johnson (red.), Musiken i Sverige 2, Frihetstid och gustaviansk tid 1720-1810, Stockholm: Fischer 1993.

Sarjala, Jukka, ”Det angenämaste och oskyldigaste tidsfördriv : musik och sällskaplighet i Åbo i slutet av 1700-talet”, Historisk tidskrift för Finland 2005: 2, s. 185-198.

Sarjala, Jukka, Music, morals, and the body: an academic issue in Turku, 1653-1808, Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society 2001.

Wolff, Charlotta, ”Musikkultur och musiksmak i 1700-talets Sverige: ett bidrag till lyssnandets historia”, Historisk tidskrift för Finland 2015: 4, s. 420-452.

Translation: Susan Sinisalo

The article was published in the booklet of The Anders Chydenius Collection album (ALBA ABCD 449) in 2020.